What is a great example of a personal statement for law school?

A personal statement can massively improve your chances of getting accepted to a top law school.

And today, I’m pulling back the curtain to share five exceptional law school personal statement examples that not only worked – they helped my clients get into some of the most competitive law schools in America.

Even better? I’ll reveal exactly why one of them succeeded despite the applicants’ low GPA and how you can apply these same principles to your own statement.

Read on!

Key takeaways:

- A compelling personal statement can overcome low stats and get you into top law schools. Real examples show that applicants with below-median GPAs were admitted to T-10 schools because their essays stood out.

- The best statements combine personal storytelling with clear legal motivation. Each example ties a specific life experience to a well-defined reason for pursuing law, showing both heart and strategy.

- There’s no single formula—but authenticity, focus, and revision are non-negotiable. Every standout essay starts with a unique story, follows a clear theme, and goes through multiple rounds of editing.

Admissions Consultant Credentials

Mara Freilich

Law School Admissions Consultant

Former civil litigator · University of Pennsylvania Law School (J.D.)

University of Pennsylvania Law School Alumni Page

Learn more about Mara Freilich, Law School Admissions Consultant.

If you want personalized guidance on crafting a law school personal statement that fits your profile and target schools, learn more about my law school admissions consulting here.

The top law school personal statement examples:

- What to include in your law school personal statement

- Example 1

- Example 2

- Example 3

- Example 4

- Example 5

- How to write a law school personal statement

What should be included in a law school personal statement?

Your personal statement is more than just another application component – it’s your first impression.

While your GPA and LSAT score speak to your academic abilities, your personal statement reveals who you really are beyond the numbers.

Think about it this way: The admissions committee is looking for the next generation of exceptional lawyers. They want to see evidence that you:

- Can weave a compelling narrative that flows naturally and needs minimal explanation

- Have a clear, convincing reason why law school is your logical next step

- Demonstrate sharp critical thinking skills (a non-negotiable for successful attorneys)

- Will contribute something valuable to their school’s community

And here’s a secret most applicants don’t realize: Your personal statement can absolutely make up for less-than-stellar numbers. I know because my own personal statement helped me get into Penn Law despite scores below their median.

Now that you know why they’re so important, let’s look at some law school personal statement examples.

Law school personal statement examples (with analysis)

Ready to see what a strong personal statement looks like?

Here are five law school personal statement examples that worked – and why.

Law school personal statement example 1

This is an example of a personal statement my client Emily wrote (her name is changed to protect her privacy, everything else is true).

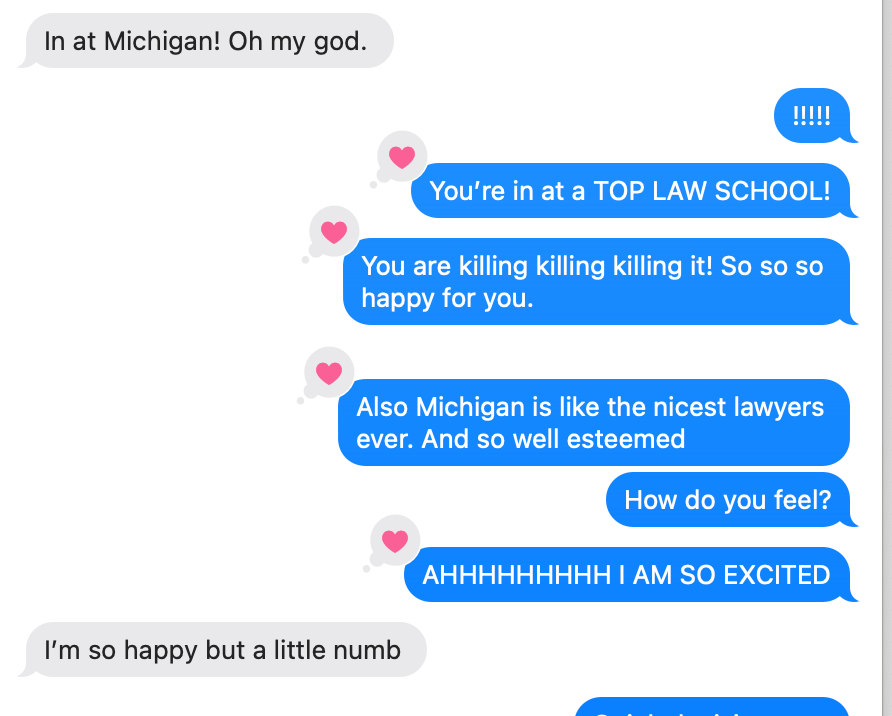

Emily had a serious drawback when she applied to law school; her GPA was significantly below all T-14 law school medians. So her personal statement really had to shine.

And by focusing on her statement, Emily was able to get admitted to a T-10 law school – a far better law school than what she “should” have been able to get admitted to if she’d only focused on her stats.

Here below, I first break down her background and admissions outcome and then share her personal statement.

Stats

- 3.2 GPA, 171 LSAT

Background

- Out of undergrad for two years. Worked as a Visitor Services Associate at a major art museum in New York for the first 18 months after undergrad, then worked as a paralegal at a well-known plaintiffs’ environmental litigation law firm for the six months leading up to her application to law schools. During undergrad, she also interned at various art museums.

Interests

- Emily knew she wanted to go to law school to work in art restitution. This had been a long-held passion of hers: she majored in history to be able to study this, interned with various museums while in undergrad, and wrote her thesis on the restitution of Nazi art.

Law school goals

- T-14 law school with opportunities specific to art restitution.

Challenges

- GPA significantly below all the T-14 schools’ medians

Admissions outcome

- Will be attending the University of Michigan Law School, a T-10 law school with specific opportunities in art restitution.

- Emily was admitted despite her 3.2 GPA being significantly below Michigan’s median 3.84 GPA, and her LSAT just reaching their 171 median. She killed it!

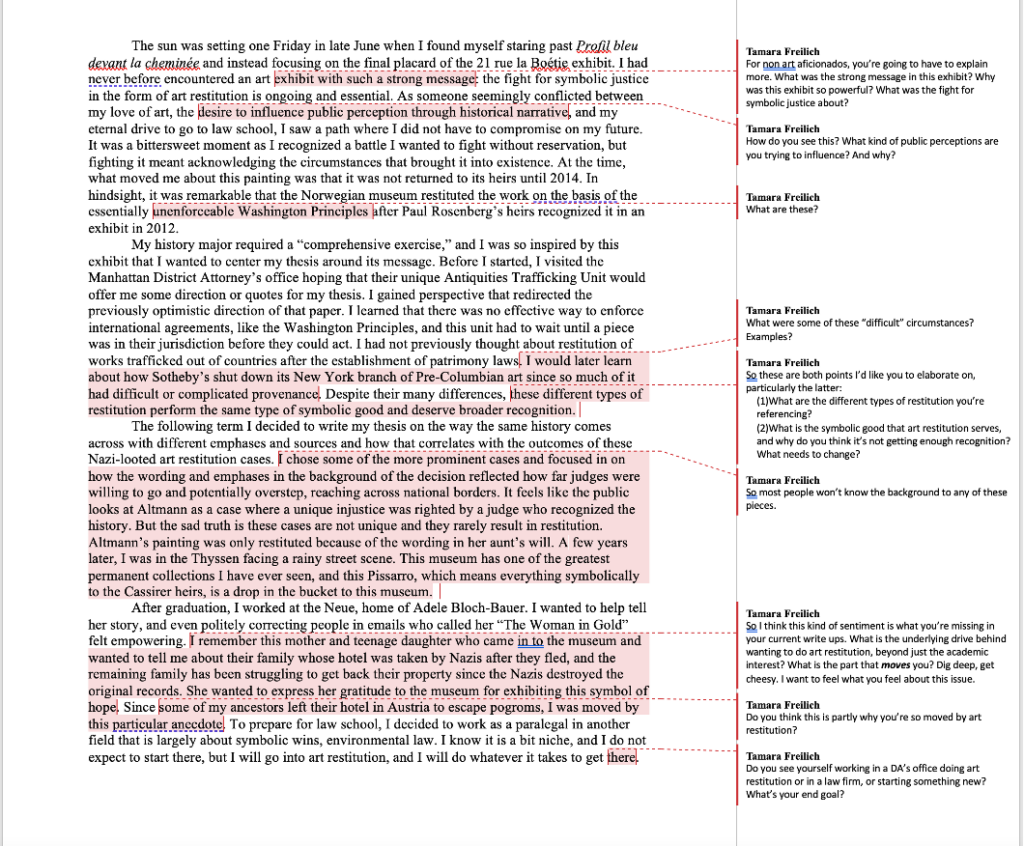

Here’s Emily’s initial draft, for reference:

“I grew up feeling connected to my parents but detached from cultural roots. My parents came from Jewish and Catholic traditions, so they raised me with a little of both. When it came time to do family trees in elementary school, I was lost beyond my grandparents’ generation. My mother reached out to my great-aunt Terry, the matriarch of my mother’s side, and thanks to her I know the story of one branch of my family tree: the Lauterbachs, Austrian Jews who fled after a pogrom, leaving behind their successful hotel. This is the oldest story that I have about my ancestors, and I cling to it as part of my identity.”

Why it works: This opening immediately establishes Emily’s personal connection to her theme. Notice how she uses a specific, relatable moment (the family tree project) to draw us in while introducing her broader search for identity.

“In college, I pursued a degree in history to learn and tell other people’s stories, and in small ways, to find my own. Given my long-held interest in art and museums, I explored art history, but the academic perspective felt too detached, and I preferred using art as evidence or context in history papers, rather than as the subject.”

Why it works: Emily strategically connects her personal background to her academic choices. We immediately understand that her degree wasn’t random—it was part of a deeper search for meaning. This shows thoughtfulness and intentionality.

“I was always grasping at things tangentially related to my weak sense of family history, so when I learned about the famous Adele Bloch Bauer I— the painting at the heart of a struggle between a Holocaust victim’s heir and a national Austrian museum, depicted in the “Woman in Gold” film—I clung to the story. I struggled to understand why there had been so much resistance to do what clearly seemed like the right thing. I was perplexed that there had been no clear avenue for families hoping to recover their looted art, searching to find a piece of their lost identity and stolen pride. Why had it taken decades for the pride of the Belvedere Museum in Vienna to be recognized by her real name and returned to her rightful owner?

I felt this same frustration when visiting 21 Rue de la Boétie, an exhibition in homage to French Jewish art dealer Paul Rosenberg—who represented Léger and Matisse among others and was forced to flee Paris in WWII, leaving behind many paintings to be stolen, destroyed, or sold by the Nazis. The last room of the exhibit contained a painting that had just been returned to his estate from a Norwegian museum a year earlier, and the plaque spoke about the ongoing efforts to find and recover additional works. Reading about how heirs were still, decades later, having to fight to recover what was rightfully a part of their family history, a part of their identity, left me furious. It felt like fate; as I was nearing the end of my quest for a senior thesis topic, I had found something that combined history, art, and justice, along with my personal search for identity.”

Why it works: This is where Emily’s statement truly shines. She’s no longer just discussing art—she’s connecting it to complex legal and moral issues. Her emotional response (“left me furious”) shows genuine passion, while her critical thinking about the injustice demonstrates the analytical mind law schools crave.

“Hoping to get a quote for my senior thesis on the upward trend of restitution in cases of Nazi-looted art, I met with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, who track down looted antiquities from war-torn or impoverished countries. The head of the unit told me that the landmark international agreement to return stolen works, known as the Washington Principles, was unenforceable and not self-policed, in his blunt words, “useless.”

Another problem that I encountered in my research was that the people holding these works often fail to appreciate their symbolic value. For a museum, these paintings are valuable works by famous artists. But for those whose heritage, ancestors, or past, is tied to an object, the value is primarily its history. A work of art cannot be separated from its past, and as a physical object, it comes to represent the people who cherished it. For me, restituting a work is a way of honoring those people. Choosing not to restitute a work legitimizes the direct and intentional dehumanizing of the Nazi regime. This result and its implications are unacceptable.”

Why it works: Emily took initiative by meeting with the DA’s office, showing drive and genuine interest. The direct quote brilliantly illustrates how current legal processes fall short—creating the perfect setup for why someone like her needs to get involved.

“It is to this end that I am seeking a law degree. I intend to be an attorney who represents heirs of stolen, looted, and missing works. While restituting art can never bring back the millions of lives lost in the Holocaust or hold accountable those who were guilty or complicit in the looting, it can still provide a small glimmer of hope, a way to honor the dead along with the survivors and repair a missing piece of an heir’s identity. It remains a way to disrupt the results of the original looting, a small right in the face of unspeakable wrongs.

I envision starting my career as a litigator in an art recovery practice group. Through these cases I will bring to light the stories of the individuals tied to these works and ensure that their stories are always told when their works are displayed. I intend to spend my career contributing to the eventual paradigm shift at which point museums and individuals will always feel obligated to restitute looted works.”

Why it works: Emily’s “why law” moment feels powerful because it emerges naturally from her narrative. Her clear, specific career vision shows the admissions committee she has direction and purpose. This isn’t just a vague interest—it’s a deeply personal mission with a concrete plan.

Law school personal statement example 2

My client P.S. crafted this statement for Harvard Law, weaving a personal health crisis into a compelling case for pursuing legal reform:

“I grew up in a home plagued by alcoholism. My siblings and I lived perpetually at one end of the spectrum or another—some days showered with almost every gift we could think of, and on others coming home to find the electricity or water shut off due to unpaid bills.

While my home life was akin to a swinging pendulum, unclear of where things would land on any given day, I had a steadiness within myself, rooted in my own proprietary blend of boldness and confidence in my ability to seek out knowledge and use it to create opportunity.

In middle school, after learning about the Magna Carta, I researched legal templates to draft a contract limiting the powers of a club’s micromanaging teacher-advisor—and convinced her to sign. In high school, I sent over 200 cold emails until I was offered a research internship to pursue my interest in biomedical research. And after designing a free curriculum to teach creative writing in schools whose art programs had been cut, I chased down state legislators to disseminate policy proposals I had written to institute low-budget creative writing programs—and got my proposal in front of the School Board.

At the beginning of my undergraduate career at Stanford, my initial plan to build on my biomedical research interests to be a physician quickly felt lacking. I knew I was missing something when I envisioned myself as a doctor or researcher, but I felt unwilling to let go of my connection with medicine.

As it happened, medicine wouldn’t let go of me, either.

In my sophomore year, my now-sober dad was diagnosed with end-stage cirrhosis of the liver.

The fallout was immediate, both emotionally and strikingly, monetarily. The aftermath of his diagnosis took me outside of my own sphere and opened my eyes to the failings of the complex dynamics that govern our healthcare system. My family was fully insured, yet we faced considerable difficulties paying for his unexpected hospitalizations. My search to better understand my family’s situation led me, still in school, to enroll in coursework focusing on the inner workings of the U.S. healthcare system. Quickly, I became attuned to the plight of patients just like my dad without the financial resources to support their care, and their quest for even a fighting chance against diseases just like his.

The patient journey and the systems that govern it soon became an academic passion of mine, and I amended my undergraduate education to make this my new focus. As a global health major, I put my own frustrations with what I saw as an inhumane system of profit over people to work and explored designing solutions to increase patient access to care: I created a low-budget proposal for malaria border checkpoints to improve surveillance between Indian states, lead-authored a study on representation of low-income countries in global health academia, and advised cash-strapped Medicaid hospitals looking for ways to finance more effective service for their millions of homeless and low-income patients.

Through my experiences with the titanic issue of inequity and inaccessibility in for-profit health systems across the globe, I discovered something even larger than my personal desire to better my and my family’s lives: purpose. I felt an immense sense of fulfillment by dedicating my time and energy to creating solutions for others rather than myself and knew I wanted to serve through legal reform.

While I solidified where I wanted to make an impact long term, my family continued to grapple with my dad’s deteriorating condition, as it became clear he would not survive without a transplant. Over months of searching for possible donors in vain, I saw my dad nearly lose his life on “the list” waiting for a new liver. It is not lost on me that his successful eleventh-hour transplant was a stroke of pure luck.

Many others are not so lucky, though no less deserving of care than my own family.

This has only deepened my resolve to find better answers for patients less fortunate than my dad.

Now, I aim to go up against the broken systems that create these realities. From my time consulting for Medicaid hospital affiliates to my current role advising for-profit healthcare litigants, I’ve learned that this will require an effective management of the transition from fee-for-service healthcare models towards value-based payment solutions. Success in this pursuit requires a balance—creating stable non-monetary incentives for high-quality treatment and prevention of illness without sacrificing immediate access to care for all patients regardless of background. I seek a legal education that provides me with an intellectual and practical experience to hone my approach to reform and further define this balance.

I intend to begin my career as a healthcare attorney, working directly with institutions to develop a deep understanding of the delicate nuances of the healthcare system. My years in practice will equip me to bring this knowledge to an academic or legislative role later in my career, where I intend to author policy that creates a system motivated by the value of human life and health, not just financial gain.”

The statement effectively connects personal adversity to professional purpose, offering a logical progression from experience to education to career. It shows both emotional intelligence and analytical thinking—a powerful combination for a future attorney.

Law school personal statement example 3

Here’s an example of a great personal by my client M.O. who got accepted to NYU Law:

“Two summers ago, my house was alive with clanging pots and scuttling dogs by 5:30 a.m. every morning. By 6:30, I was sitting in the car, younger brother dozing off in the back seat as we drove across town to Bio-Med devices. By 7:10 (and not a minute later), I was waving goodbye as he disappeared into the ventilator department and finding my spot on the cramped circuits assembly line, gloves on, ready for another day of work.

If you had told me in January of 2020 that I would spend months of my sophomore year working at a medical device factory in Guilford, Connecticut, I would have probably laughed. During my interview for that assembly position, the factory manager had paused and looked at me skeptically. He asked, “Have you ever . . . held a wrench before?” The answer was no. In fact, I had never stepped foot in a mechanic’s shop before, never mind a factory. But after spending hours watching news coverage about rising COVID case rates and worsening supply shortages, I had felt an overwhelming sense of urgency. I was lucky enough to be healthy and able-bodied, and I needed to be doing something, anything, to help. I couldn’t watch from the couch when there was such a clear, pressing need, and I had the power to contribute.

The next day, I applied to the grocery store, the pharmacy, and every other essential business in my tiny town. It just so happened that I lived next to Bio-Med devices, the largest breathing equipment manufacturer in the state. I applied, and they called back right away: their breathing circuit team, previously just three people, was now over twenty strong and still struggling to fill an unprecedented number of orders. I was on the line by 7:10 a.m. the next Monday.

Only a few weeks later, I was building dozens of circuit models from memory, hauling boxes twice my size, deftly using industrial machinery, and teaching an endless stream of new hires to do the same. By the end of that summer, I had built over three thousand disposable breathing circuits by hand and shipped them to dozens of overwhelmed hospitals across the country.

I have always felt a need to be helping where it’s needed most, and my sophomore summer, that need just happened to be at the medical device factory down the street. However, this burning desire to be doing and helping is a mentality that I carry into every aspect of my life.

Starting in late high school, I watched my grandmother battle lung cancer after decades of cigarette smoking. I had always viewed her illness as the tragic consequence of an unhealthy lifestyle choice. While not incorrect, it wasn’t until I began taking health policy classes for my undergraduate degree that I saw the full picture of her declining health.

I distinctly remember my first day of class sophomore year, sitting in a packed lecture about addiction, watching as cigarette advertisements from the 1950s flicked across the screen. At a time when there was already a documented, albeit private, consensus about the carcinogenic effects of cigarettes among tobacco industry insiders, I was horrified to see cigarettes being marketed as a mood tonic, a sore throat cure, and, most disturbingly to me, a harmless diet aid. It suddenly occurred to me that it was no accident that my grandma, at the time an admittedly weight-conscious teenager, had started smoking. Her cancer was far from an accident; it was an intentional exploitation of known societal expectations and gender norms. The tobacco industry sold my grandmother a fantasy with full knowledge that she would likely pay with her life.

Sitting in the lecture hall that day, I was overwhelmed by a deep sense of urgency: Was this type of fatal corporate manipulation still happening? How was no one being held responsible? And, alarmingly, were there products being sold to my generation that would one day kill us? Disturbed, I resolved to learn more and find a way to act.

From that point on, I invested my time both inside and outside the classroom to understanding this blatant commodification of human health. I completed research projects on tobacco policy, went into local inner-city schools to teach tobacco awareness curricula, and dedicated the majority of my work at the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program, a non-profit policy research institution, to researching how think tanks have historically facilitated corporate influence in the tobacco and alcohol policy space.

While I initially thought that a career in health policy would provide me with the best opportunity for impact, the more classes I took and research I did, the wider my eyes opened to how pervasive and ongoing this type of corporate exploitation really was and continues to be. It was then that I realized a policy career would not be enough, and only a law degree would allow me to directly hold these predatory corporations accountable.

Despite the fact that corporate manipulation of consumers has had a massive and measurable toll on public health, corporations have yet to face consequences sufficient for deterrence: During the very years I was discovering this academic passion, e-cigarette companies used sweet flavors, young actors, and bright advertisements to get children all over the country hooked on “totally safe” nicotine-riddled vaporizers that I am certain will one day take lives. An interest that started with my family has now grown into a passion for holding exploitative institutions accountable for prioritizing profit over people, and I know that a legal career is the best way to maximize my impact: I truly believe that this is where I am needed most.

I intend to use my law degree to advocate on behalf of the communities and individuals whose health and well-being is wrongfully sacrificed for a corporate agenda and whose lives have been reduced to collateral damage in an ongoing pursuit of profit. I envision pursuing a career as a mass torts litigator, perhaps focusing on toxic torts. I foresee starting my career working at a plaintiffs’ impact-litigation firm and then bringing the knowledge I gain from litigation into a more policy-related role, such as for a governmental agency or a policy-focused non-profit.”

This personal statement illustrates her passion and purpose while describing why she’s an ideal law school candidate.

Law school personal statement example 4

This personal statement example is by one of my clients who applied to Columbia Law School:

“Over the course of my undergraduate experience, I have held a variety of roles in both journalism and politics. Although I loved diving into social justice issues and public policy, I felt a growing sense of frustration as I increasingly faced an inability to make substantial change. My desire to be a direct force of progress, coupled with my discovery of a passion for criminal justice, led me directly to law.

Knowing I wanted to delve deep into social issues, I applied and was accepted into the school of journalism. My junior year, I took a job working as an on-air reporter for a CBS-affiliate news station, eager to explore my passion for news. One of the most challenging parts of my job was having to cover polarizing ideological conflicts—like an anti-gun control rally or a protest against Covid safety measures—where I personally held opposing stances. I learned to listen, to find commonality even with those I strongly disagreed with, yet I still felt frustrated by the expectation that I remain neutral and unbiased. I wanted to be an advocate, not a reporter.

My frustration culminated when I was assigned to report on a protest against the treatment of immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. I spoke with the woman who had organized the event, a Mexican woman who had immigrated to America when she was a teenager. She told me how afraid she was for the safety of her children, recounting the experience of seeing family members killed in front of her while trying to cross the border. Although I was aware of the abuses of power by ICE at the border and had read reports of the horrific conditions of immigrant detainment camps, hearing her story illuminated the issue in an entirely new way for me—an issue that had previously felt far removed from Wisconsin. I was excited to share her story and hopeful that it would resonate with viewers in the same way it did for me.

When my editor decided to cut her story from the air, citing it as being “too heavy,” I was shocked. I thought the goal of journalism was to expose the harsh realities of our political systems, not intentionally shield people from it. I pushed him to reconsider, and ultimately the story was included. I felt relieved after what felt like a momentary win, but I knew it was just that—momentary. I began to realize that the change I wanted to make couldn’t be done with journalism alone. I didn’t just want to be the one sharing people’s stories; I wanted to be the one in their corner, fighting to defend them.

My desire to enact change pushed me to explore politics—what I thought would be a chance to directly confront the policies that I saw failing others. Yet working as a legislative intern for a Democratic State Senator, in a Republican-controlled state made progress feel out of reach. Witnessing state representatives put personal feuds and power dynamics ahead of the best interests of their constituents made me realize that the political process was too protracted to enact the change I was seeking.

I continued to report on local issues, still struggling with how to implement change. For a semester-long reporting project, I focused on policing, drawn to the issue by a string of recent violent crimes on campus. I spoke extensively with local police officers as well as student and community groups about their issues with law enforcement. Over the course of the semester, I also began to look outward, becoming fascinated with how the issues in my community were being reflected on a national scale. I realized that many of the concerns my fellow students had, like racial profiling and unnecessary uses of force, stemmed from systemic issues that went beyond just my campus.

It was my proximity to issues of policing at a community level that sparked my continued passion for criminal justice reform. The more facts I uncovered—about the disturbing number of Americans incarcerated, and even larger amount on probation, trapped in cycles of recidivism—I recognized how broken our system is. I knew I didn’t want to just report on these facts; I wanted to act.

Once I realized that criminal justice reform is what I am truly passionate about, my uncertainty of what path to take faded completely. I want to fight for the voiceless, reform the broken system, and represent those who have been lost in it. To do this, I need a law degree. With a law degree, I will be able to challenge the statutes that fuel the broken criminal justice system, and I can make the direct change I have so long been yearning for, without the barriers I faced in journalism or politics. I envision starting my career working directly with individuals in the criminal justice system, perhaps as a public defender. I then intend to transition my career to challenge the laws that keep people within the system, utilizing a powerful combination of storytelling, legislative advocacy, and litigation, perhaps for an organization such as the Equal Justice Initiative or the Buried Alive Project.”

Law school personal statement example 5

And here’s one on a specific theme – foster care:

“Besides the farmland, Khartoum and Belvidere are quite different. I immigrated to America at three years old. Despite the chaos in my homeland of Sudan, I only experienced war on vacation. By the time I turned eleven, Baba worked his way up from a taxi driver living in Chicago’s Section 8 housing to becoming an aerospace engineer and buying our first house.

But when my parent’s disciplinary measures caught the attention of Child Protective Services our American dream turned into a nightmare. My younger siblings and I entered the foster care system, shuffling between different group homes and schools, often separated. My hunger never synced with my scheduled meals and the fridge and kitchen cabinets stayed under lock and key. I witnessed, more often than not, that the undoubtedly complex, multilayered system, tasked with protecting the most vulnerable, was far from equipped to surrogate childhood.

Joining the high school swim team was my only method of control, but Coach and I were always the last ones. Ride issues led other foster teens to quit after-school activities and I could not bear joining them. Eventually, I told my Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) worker that no matter how many times I reminded the staff in the morning, no one picked me up after practice. When she promised to get me a ride, I encouraged others to tell their CASA workers why they quit attending clubs after school. The influx of complaints caused a stir for social services.

At fifteen, I found myself testifying in court. “She’s been acting up, quite the instigator,” my social worker alleged in response to the judge requesting a daily van pick-up to begin for anyone in afterschool activities at my shelter. On Monday, I finished swim practice to find a ride was waiting for me. Many others rejoined after-school activities, and I became known to social services as the shelter “instigator”.

“Instigating” landed me in student government as a college freshman at the University of Illinois. While attending a “Lunch and Learn ” at the Native American House for a free meal, I learned the racial ramifications of Chief Illiniwek–the school’s current mascot–on my Indigenous colleagues. Norms of society have evolved to the point where Blackface retains the ability to shock, but Redface in the form of a mascot is so embedded in American culture that people hardly flinch. The active presence of mascot Chief Illiniwek, despite forced retirement by the NCAA in 2007, implied a tolerance for discrimination against Native Americans and their denial of equal opportunity to education and full enjoyment of public facilities that are protected by law. How backward, that on their stolen land, Native students were so dehumanized.

When I analogized Redface to Blackface, more of my colleagues began to understand the harms of Chief Illiniwek. My arguments strengthened and each conversation motivated me for the next one. Organizing became my next tool in instigating change.

Elected student body president my third and final year, I built a coalition and leveraged power to support Indigenous students using a combination of protests and negotiation. Despite the request of Native students, the administration refused to prohibit the unofficial Chief Illiniwek from leading a float in the homecoming parade. In foster care, building support in numbers is what led to our van pick up, so I knew that in numbers, allies were my best resource to build the pressure for change.

Over 20 Registered Student Organizations, 300 students, as well as the Campus Faculty Association showed up to protest in solidarity. At last, the unofficial Chief Illiniwek left, and the parade resumed without Redface. I didn’t stop there.

Understanding the parameters of The First Amendment, I successfully amended the stadium bag policy, so the new size limitations prohibit someone from bringing the Chief Illiniwek costume into stadiums and outfits in the bathroom. My initial desire to push the needle on the racially stereotyped mascot led to a shining example of forged community and solidarity six months later, when the administration finally enforced the removal of the Chief Illiniwek logo in all facility and operation areas.

I have been exposed to the world on extreme sides of the spectrum, existing for a time as a ward of the state of Illinois with no power to represent 48,000 students. I am from the poorest and richest nations in the world. My extremities primed me to thrive when challenged at the highest level, serving the 44th and 46th Presidents of the United States.

When foster kids and Indigenous communities are set aside, “instigating” is essential to promoting and protecting our rights, and on a broader scale, it is lawmakers who have the potential to drive effective change. I saw this when working for President Obama, who taught me that ordinary people in local communities can do extraordinary things. Planning programs for hundreds of changemakers around the world, I witnessed firsthand how values-based leadership advances the ability to enact change. And significantly, I saw how all these changemakers had something in common: the law as their tool to drive effective change. It was then I realized that to continue my “instigating,” I needed a law degree.

I believe the judicial system, through litigation specifically, is the most effective mechanism to promote social change. By understanding the law and the complexities of different legal and institutional forces, and integrating the communities I serve into the lawyering process, I intend to pursue law reforms and change discriminatory government policies. As the next step, legal education will provide me with the intellectual and practical experience to inform present discussions of how rights are defined and advocated for. I foresee starting my career in a policy-related role in the federal government, authoring and aiding in the full legislative process. After years in practice, I plan on bringing my policy knowledge to an advocacy organization firm, such as the ACLU, to build and plan impact litigation cases at the grassroots level.”

How to write a good law school personal statement

After analyzing all these successful examples, you’ve probably noticed some common threads. Here’s my proven process for creating an equally compelling statement:

Step 1: Find your unique topic

You don’t need a dramatic life story. You just need an authentic one that connects meaningfully to your pursuit of law.

Start by asking yourself:

- What aspects of my character set me apart? Are there specific experiences that showcase these traits?

- What wouldn’t be obvious about me from my transcripts and resume alone?

- Why am I genuinely drawn to law school? (Dig deeper than “I want to help people” or “I like to argue”)

- What specific impact do I hope to make as a legal professional?

For more, check out these guides for more on choosing a topic:

- Top Personal Statement Topics + Ideas

- Personal Statement Topics to Avoid

- Personal Statement Mistakes

Step 2: Structure your personal statement

The best personal statements read like well-crafted narratives:

- Begin with a compelling hook – A specific moment, vivid image, or thought-provoking question works better than broad statements.

- Build the middle with growth and insight – Show your development through experiences that shaped your thinking and values.

- End with clear purpose and vision – Connect everything to why law school is your logical next step and what kind of student/lawyer you’ll be.

Remember: Your statement should be one cohesive story, not a collection of disconnected achievements.

Step 3: Revise and edit your personal statement

Your first draft is never your final draft. In fact, the most successful statements I’ve helped craft went through 5-10 revisions.

After writing your initial draft:

- Set it aside for at least 24 hours

- Review for narrative flow and focus – Does everything connect logically?

- Cut anything that doesn’t strengthen your central message

- Polish for grammar, spelling, and word choice

- Get feedback from someone who will be brutally honest (not just supportive)

Pro tip: Read your statement aloud. If you stumble over a sentence or run out of breath, it needs restructuring.

Frequently asked questions about personal statement examples

What should be the opening sentence of a law school personal statement?

How should you start your personal statement? The key is to introduce your topic fast and then build your story. If you include a lengthy introduction, you won’t have as much space to fill in your story… And frankly, you’ll lose the admission officer’s attention.

Start with an engaging introduction that clearly shows the reader what you will be talking about and keep them interested in reading the rest of your statement.

What not to say in a law school personal statement?

You’ll generally want to avoid any overused personal statement topics. These are historical or political events (unless you were personally affected by them in a meaningful way – just like Emily had a family history that made her interested in Nazi art lootings), athlete stories, generic study abroad stories, high school events, creative writing-type essays, or relying on a difficult story as a “crutch” instead of using it to build your cohesive story.

How long should a law school personal statement be?

The length of your personal statement depends on the law school, but the typical length is two pages. Check what law schools state about their requirements to understand how long your personal statement should be.

Next step to getting accepted to your dream law school

Remember what we’ve learned from these examples:

- Your personal statement doesn’t need to feature extraordinary circumstances

- It does need to tell a thoughtful, authentic story that connects meaningfully to your pursuit of law

- The best statements show both emotional intelligence and analytical thinking

- Specific, forward-looking career goals demonstrate seriousness and direction

Need help bringing your personal statement from good to great?

I’ve helped hundreds of students get into top law schools—even with numbers below school medians. Find out how I can help you craft a standout statement that showcases your unique potential as a future attorney.

Learn more about working with me here.

Read more: